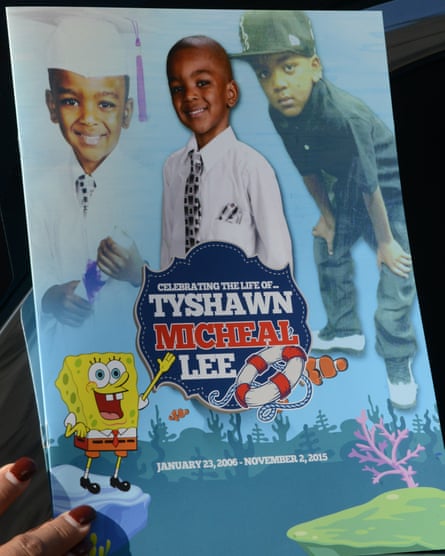

The day he was killed, Tyshawn Lee had been playing on the swings at a local playground. It was four in the afternoon, and his grandmother’s house was barely a block away.

Children are murdered with distressing frequency in Chicago, often in places of safety: a mother’s lap; a Fourth of July celebration; a sleepover at a friend’s house. But Tyshawn’s murder was different. The nine-year-old was executed.

A 21-year-old gang member had approached him, dribbled the fourth grader’s basketball and offered to buy him something at a local store, officials said. The two of them were seen walking into the alley. There, officials said, Dwright Boone-Doty had faced the little boy directly and shot him multiple times at close range. Part of Tyshawn’s thumb was missing, as if he had raised his hand trying to stop the bullets.

Police said Tyshawn had been targeted on 2 November because of his father’s gang connections. The murder stunned the city. How had one of America’s greatest cities let violence spiral so out of control that a fourth grader could be assassinated in broad daylight?

Boone-Doty was charged with murder earlier this month. Both he and another man allegedly involved in Tyshawn’s killing had been in custody since mid-November. “We hope this development will bring some level of closure to his family and friends,” Chicago’s interim police superintendent said at a press conference.

Instead, hours later, Tyshawn’s 25-year-old father, Pierre Stokes, aimed a gun at the girlfriend of one of the gang members allegedly involved in his son’s murder, said “I’m going to kill you, bitch,” and started shooting, a prosecutor said. The woman survived with only a grazed face. Two of her nephews went to the hospital with bullet wounds.

This escalating spiral of retribution on Chicago’s South Side – drawing in mothers, grandmothers, girlfriends and children – comes as both the city and the state are in crisis. Chicago public school teachers are planning a city-wide strike. The city has been wracked by a state budget standoff that is decimating social service programs and by continuing public outrage over how the police department and city officials responded to the killing of 17-year-old Laquan McDonald by a police officer.

Since January, gun violence in Chicago has spiked. The city has seen twice as many shootings this year as it did last year, and nearly twice as many homicides. If the current trend of violence continues, the state’s attorney said last month, Chicago is on track to see 700 homicides this year – 200 more than in 2012, when the number of deaths sparked outrage and vows of reform.

Asked to explain the rising violence, a spokesman for Chicago mayor Rahm Emanuel pointed to crime trends in St Louis and Baltimore, where protests and outrage over police violence towards black citizens were accompanied by increases in shootings and homicides. The mayor’s office suggested police officers are afraid of being “the next viral video” and that officers were “aware of gangbangers and criminals who are more emboldened given the environment”.

As Chicago police officers describe themselves as being under attack, some kinds of proactive policing activities have dropped. Total arrests are down about 27% this year compared with the same period last year, according to official statistics. Investigative stops are down about 80%. Other kinds of arrests have not slowed: arrests for more violent crimes, including murder, are up since last year, a police department spokesman said, and gun arrests have remained flat.

The data is far from conclusive. But Baltimore saw a similar pattern after the Freddie Gray riots: police officers feeling betrayed by city officials. A sudden drop in arrests. A sudden spike in shootings and homicides. The bloodshed after Gray’s death left Baltimore with more murder victims than the city had seen since 1993.

If Chicago cannot slow down the rate of shootings, some residents worry, the city may be headed towards a level of violence it has not seen in decades.

Chicago is one of the most racially segregated cities in the US. It’s possible to spend an entire day in Auburn Gresham, the neighborhood where Tyshawn was killed, without seeing a single white face – except the faces of white officers rolling by in a squad car.

The segregation was purposeful, the legacy of decades of discriminatory housing policies. Even today, neighborhood residents say, they see clear differences in public schools, economic investment and opportunity. In white neighborhoods, “you have everything that is set up for success,” said Keishana Mahone, 41, who lives in Auburn Gresham. Here, she said, “you see everything set up to fail.”

Even in neighborhoods struggling with poverty and unemployment, it’s a very small percentage of people driving most of the violence. Researchers studying non-fatal shootings in Chicago found that most of the violence occurred within a loose network of people that made up about 6% of Chicago’s total population. Within that network, they found, violence seemed to spread like a virus. The more connections people had with shooting victims, the more likely they were to be a victim of a shooting themselves.

The people at highest risk of being shot in Chicago were black gang members, followed by Hispanic gang members. Chicago’s gangs used to be powerful, highly structured organizations. Today, those gangs have fractured into tiny factions whose membership is defined by the span of a few neighborhood blocks. In Auburn Gresham, officials said, Tyshawn’s death was part of a long-running gang war between Killa Ward, a faction of the Gangster Disciples, and the Bang Bang Gang/Terror Dome faction of the Black P Stones.

Two weeks before Tyshawn’s murder, officials said, Boone-Doty had opened fire on a car that he thought held a rival gang member. A prosecutor said he later claimed “he did not even know who was in the car” when he shot. All he had seen was the man’s dreadlocks. The man survived. Nineteen-year-old Brianna Jenkins, who was also sitting in the car, did not.

The police department’s clearance rate for murder is only 31%, meaning that the majority of murders go unsolved and unpunished.

In Auburn Gresham, some local residents felt that local police officers had a racially biased approach to dealing with young men. “Every black boy is not a criminal,” said Malone, whose son, a singer who grew up in the neighborhood, was a contestant on The Voice. But a more common complaint in the neighborhood was police officers did not patrol aggressively enough, or in the right places. Mahone said she was often frustrated to see two or three squad cars in the parking lot of a local CVS, or parked on the same neighborhood side street, rather than patrolling in more dangerous areas.

In Dawes Park, a group of teenagers playing basketball pointed to a police cruiser stopped nearby. It was a bright, chilly afternoon, and, except for them, the park was nearly empty. Wasn’t there somewhere else that needed more police attention?

Chicago’s police department has swung from a dramatically high rate of investigative stops to a dramatically low one. In the summer of 2014, the American Civil Liberties Union found, Chicago police officers made more than 250,000 stops that did not lead to an arrest – a rate of stops four times higher than New York City at the height of stop and frisk. The vast majority of those stopped were African American, and the ACLU found officers had failed to report a legal reason for the stop in half of the incidents they analyzed.

In response, the department agreed to require officers to fill out a detailed, two-page form for every person they stopped, a requirement officers have complained is burdensome. Since the new requirements went into effect on 1 January, investigative stops have plunged 80%.

Representatives of the ACLU and the city’s police union said they did not think there was a direct connection between the decrease in stops and the spike in violence.

“We’ve got to be very careful with police officers being blamed for crime increasing,” said Dean C Angelo Sr, the president of Chicago’s Fraternal Order of Police. “They’re blamed when they search people and then they’re being blamed when they don’t search people. What does the community want?”

Angelo said the political aftermath of the Laquan McDonald protests had created an “unprecedented” environment for police officers.

“They don’t want to be the next YouTube video,” he said. “They’re telling me: ‘Every single traffic stop or street stop, I’ve got 15 cellphones filming me.’”

“I don’t know how much more people want to impact policing – people that have never done policing, by the way – before they realize that they’ve curtailed the opportunity to be proactive,” Angelo said.

One Chicago officer, who was not authorized to speak to the media and spoke on condition of anonymity, said that the so-called “YouTube effect” was not the real reason for decreased police initiative.

“If you’re doing your job in the right way, guys aren’t afraid of being videotaped,” the officer said. “Guys are afraid that our administration isn’t going to back us, that special interest groups will take it and run with it and the next thing you know, you’re being charged.”

Chicago officials have long blamed the city’s violence problem on a flood of illegal guns streaming into the city and into the hands of felons. The city has strict gun laws, as conservatives often point out, but weapons recovered at Chicago crime scenes often come from states such as Mississippi or neighboring Indiana, which have much looser laws.

Last week, nearly 200 people came to Saint Sabina, a church in Auburn Gresham, for the Chicago premiere of a new gun control documentary, Making a Killing: Guns, Greed and the NRA. The film juxtaposed the stories of shooting victims with examples of the wealth and influence of National Rifle Association leaders and firearm industry executives. Its policy proposals – including background checks for every gun sale – were met with murmurs of approval.

Tommie Bosley, whose 18-year-old son Terrell was shot to death outside a church in 2006, said his years of being an advocate for tougher gun laws had taught him that “There’s a certain segment of society that basically values money more than people’s lives.”

“To actually see that put in your face, and have people tell you that – that’s very disappointing,” he said.

At Barack Obama’s town hall discussion on guns in January, Father Michael Pfleger, Saint Sabina’s firebrand priest, asked the president why guns could not be licensed or registered like cars.

Obama, who referred to him affectionately as Father Mike, told him gun registration was too extreme for the current political climate. “There’s just not enough national consensus at this stage to even consider it,” he said.

Chicago police officials also say the city’s court system is broken, with judges treating gun crimes too lightly. Tyshawn’s alleged killer had been sentenced to five years in prison in 2013. He served about two years and was released in August 2015. Officials have said Boone-Doty shot at least three people, including Tyshawn, in his first three months out of prison.

In an emotional phone interview, Michelle Doty, his mother, said her son was not the cold-hearted killer that news reports had made him out to be. She did not believe he would execute a child. “Did I raise my baby to be this? No. No, no, no,” she said.

She said she had struggled to get him back on the right track. They had done family counseling together. When he was in juvenile court, she said: “I went to the court system, begged to send him to boarding school, whatever I could do to get him a definite outlook on life. They literally shot me down. They told me he didn’t have enough points to go to boarding school.”

“The system has failed me,” she said, “and I am 165% sure I am not the only parent out there that was reaching for my baby for help and the system has failed.”

Doty said since the shooting she had left the state in fear for her safety, and could not say where she was currently located.

Michelle Doty’s aunt said Dwright had emerged from his stint in prison changed and bitter, but that she could not believe he would hurt a child. At her birthday party in November, shortly before he was arrested, she remembered him playing PlayStation with her grandchildren, who adored him.

“He hadn’t been around the games for a while,” she said. “They were trying to teach him how to do the joystick, and that was funny. He wasn’t doing it right.” She remembers the kids shouting at him to push different buttons. “He was trying. He couldn’t get it right, you know? He couldn’t win.”

Policing and the courts are not the only services under pressure. Illinois has not passed a budget in more than a year, leaving social service agencies and public universities without funding to carry out basic functions. Lutheran Social Services of Illinois announced in January that the budget crisis had forced it to shut down dozens of programs and lay off more than 700 staffers, nearly half of their total. Community mental health programs are being shuttered. Programs that help young people involved or at risk of being involved in the criminal justice system have “vanished”, said Andrea Durbin, the CEO of the Illinois Collaboration on Youth.

At Saint Sabina, Pfleger, who was the model for a character in Spike Lee’s recent movie Chi-Raq, said, the church had lost $1m of state funding “in an email”. Its summer jobs program, which offered 1,150 summer jobs in 2014, could only offer 350 last year, he said. A recent study from the University of Chicago Crime Lab found summer jobs programs can dramatically reduce youth violence.

Illinois has also eliminated state funding for an intervention program the Department of Justice has dubbed “promising” for reducing shootings. The Chicago Ceasefire or “Cure Violence” approach uses former gang members as neighborhood mediators. The strategy, featured in an acclaimed 2011 documentary, The Interrupters, has been replicated across the country.

Last year, Illinois abruptly froze the local program’s funding, and Ceasefire Illinois had to lay off 100 outreach workers and shut down more than 18 local Ceasefire officers, executive director Mark Payne said.

One of the shuttered Ceasefire programs was in Auburn Gresham, which laid off all six of its outreach workers last spring.

The community center that ran the program is across the street from the gas station where police say Tyshawn’s father attacked the girlfriend of a rival gang member.

When the Ceasefire program was up and running, an outreach worker had often been posted right in front of that gas station, said Joewaine Washington, who worked in the neighborhood as a Ceasefire violence interrupter for nearly a decade.

If someone had been there to calm down the fight when it first started, “It wouldn’t have escalated like that,” Washington said.

Sitting at Nick’s Gyros, a popular restaurant across from the gas station where shots were fired, Yusef Brown, 41, said the Ceasefire cuts showed Illinois’s governor was “out of touch”.

Ceasefire was “a drop in the bucket” when it came to addressing violence, Brown said, but he appreciated seeing the outreach workers and their signs around the neighborhood. “To cut one of the few programs we have that’s trying to make a difference is crazy,” he said.

In a statement, a spokeswoman for Republican governor Bruce Rauner blamed statehouse Democrats for the suffering caused by the budget crisis, and said the governor’s proposed “structural reforms” would “allow businesses to grow and create more jobs, particularly in the state’s most impoverished and high crime areas”.

“Unfortunately House Democrats are on a month-long vacation while programs like this suffers,” she wrote.

Outside Saint Sabina, a sign called on Governor Rauner to restore the programs.

Chicago was the victim of the same kind of government neglect that had poisoned the children of Flint, Father Mike said, “only there they can pinpoint it – it’s the water. Here it’s neglect, abandonment, cuts of programs.”

“The governor doesn’t give a damn about people,” he said. “He’s a businessman, and this is a business venture for him. He has somehow not realized these are not stocks, these are individuals. It’s not about the Dow Jones, it’s about Mrs Jones, and these are real people who are dying in his hands.”

Pfleger, who conducted Tyshawn’s funeral, said he thought it was irresponsible of law enforcement officials to highlight so many of the gruesome details of his murder in a public press conference.

Tyshawn’s father has “been in the streets, he’s done a lot of bad things”, Pfleger said. But any father would have been outraged to hear his child’s killer had considered torturing him by cutting off his fingers and ears.

“If this is what guys do, and then you put this kind of stuff out there on national news, you don’t think you’re going to get a response on the street?”

“The brothers on the street,” he said, believed that police “wanted a street fight”.

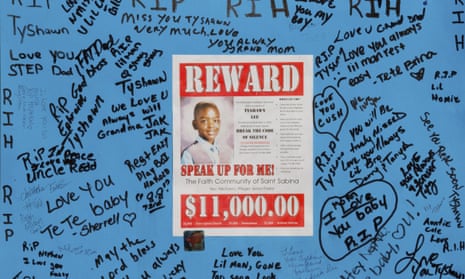

Last Saturday afternoon, a Chicago youth activist, Lamon Reccord, held a march in Auburn Gresham demanding Justice for Tyshawn. Protesters were supposed to meet on a street corner a few blocks away from the alley where Tyshawn was killed.

Reccord, 17, a high school senior, had been a ubiquitous face at Chicago protests over the last months. He had lost a friend to gun violence in 2014.

“If more than 2,000 Black people can go to a Anti-Trump Rally but can’t go to a Put The Guns Down Rally for a 9 year-old boy getting shot, having his innocent & bright future taken away from him, then people for a fact don’t just have a problem in their community, it’s in their heart,” he posted on Facebook before the event.

The turnout for the protest was small. At its peak, it drew about 25 people, including Jedidiah Brown, the activist who had been pulled offstage during the Trump rally, and Aleta Clark, who had started an anti-gun violence campaign, #HugsNoSlugs, using the platform of her popular Instagram account, EnglewoodBarbie.

Undaunted, Reccord and other protesters wove through traffic at the intersection, holding up signs. Tyshawn’s mother, Karla Lee, came to the protest along with a small group of friends. She put on a #HugsNoSlugs T-shirt and held up a sign. But she left before the march itself started, looking shaken.

By the time the march started down 79th street, there were only about 14 protesters. Seven police cars, marked and unmarked, rolled beside them, lights flashing. “This is, like, the best police escort ever!” Reccord said.

“A man is not a man, a man is not a man, a man is not a man, with a gun in his hand!” they protesters chanted.

A few cars honked in support.

Across the city, politicians and community leaders had argued that Chicago could not address rising violence without rebuilding the broken relationship between neighborhood residents and the police. But at the peaceful protest, white police officers and black protesters stood on a freezing intersection together for more than an hour with almost no interaction, other than politely negotiating the logistics of the march. The protesters chanted and held signs. The white officers stood back, chatting in pairs with each other. If a protest for a murdered boy wasn’t an opportunity to start a dialogue between police and residents, what would be?

For nine-year-old Tyshawn, so many problems had conspired against him. A cycle of retaliation where young men are drawn into violence and parents feel helpless to stop them. A city with gun control laws that don’t work because weapons flood in from other states. A police service struggling to find middle ground between oppressive force and pulling back into a defensive crouch. Small community efforts to prevent violence undone by funding cuts.

“To be honest, sometimes, I look at it, and I wonder why we don’t have more violence,” Father Mike said.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion