Herxheim (archaeological site)

The archaeological site of Herxheim, located in the municipality of Herxheim in southwest Germany, was a ritual center and a mass grave formed by people of the Linear Pottery culture (LBK) culture in Neolithic Europe. The site is often compared to that of the Talheim Death Pit and Schletz-Asparn, but is quite different in nature. The site dates from between 5300 and 4950 BC.[1] The site contained the scattered remains of more than 1000 individuals from different, in some cases faraway regions. Whether they were war captives or human sacrifices is unclear, but the evidence indicates that they were roasted and consumed.[2]

Discovery[edit]

Herxheim was discovered in 1996 on the site of a construction project when locals reported finds of bones, including human skulls. The excavation was considered a salvage or rescue dig, as parts of the site were destroyed by the construction.[1][3][4]

Culture[edit]

The people at Herxheim were part of the LBK culture. Styles of LBK pottery, some of a high quality, were discovered at the site from local populations as well as from distant lands from the north and east, even as far as 500 kilometres (310 mi) away. Local flint as well as flints from distant sources were also found.[3]

Settlement[edit]

The structures at Herxheim suggested that of a large village spanning up to 6 hectares (15 acres) surrounded by a sequence of ovoid pits dug over a duration of several centuries. These pits eventually cut into one another, forming a triple, semi-circular enclosure ditch split into three sections. The way the pits were dug over such a length of time, in addition to their use, suggests a pre-determined layout.[1] The structures within the enclosure eroded over time, and "yielded only a small number of settlement pits and a few graves".[1] These pits were either trapezoidal or triangular in nature.[4]

Mass grave[edit]

The enclosure ditches around the settlement comprise at least 80 ovoid pits containing the remains of humans and animals, and material goods such as pottery (some rare and high-quality), bone and stone tools, and "rare decorative artifacts".[1] The remains of dogs, often found intact, were also recovered.[1][3]

The human remains were primarily shattered and dispersed within the pits, rarely intact or in anatomical position. Using a quantification process known as "minimum number of individuals" (MNI), researchers concluded that the site contained at least 500 individual humans ranging from newborns to the elderly.[1] However, "since the area excavated corresponds to barely half the enclosure, we can assume that in fact more than 1000 individuals were involved".[1] The deposition of the human remains occurred only within the final 50 years of occupation at the site.[1]

Mortuary practices[edit]

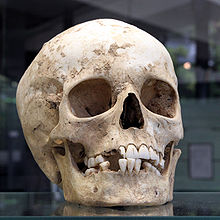

A 2006[3] study revealed the intentional breakage and cutting of various human elements, particularly skulls. Bones were broken with stone tools in a peri-mortem state (around the time of death), as is evident by the fragmentation patterns on the bones, which differ between fresh and dry (old) conditions.[5]

A 2009[1] study confirmed many findings from the 2006 study, but added new information. In just one pit deposit, this study found 1906 bones and bone fragments from at least 10 individuals ranging from newborns to adults. At least 359 individual skeletal elements were identified. This in-depth study revealed many more cut, impact, and bite marks made upon the skulls and post-cranial skeletal elements.[1] It was apparent that parts of the human bodies were singled out for their marrow content, suggesting cannibalization (see below).

Due to the fractures present on the bones being peri-mortem, the blows to the bones could have been made immediately prior (including as cause of) or soon after death. However, because of their precision placement, it seems more likely that most cuts and blows were made soon after the person's death, indicating a process of defleshing and dismemberment rather than the person being killed.[1]

Skull cult practices[edit]

Of particular note from both studies[1][3] was the peculiar treatment of the humans' skulls. Many skulls were treated in a similar manner: skulls were struck on "the sagittal line, splitting faces, mandibles, and skull caps into symmetrical halves".[3] A few skulls were clearly skinned prior to being struck, again, all in the same manner: "horizontal cuts above the orbits, vertical cuts along the sagittal suture, and oblique cuts in the parietals".[3]

The vault of the skull was preserved and shaped into what is referred to as a calotte (calvarium). During this process the brain, which is a source of dietary fat, may have been extracted. Additionally, a later study revealed that the tongues of humans were removed.[1]

Ritual cannibalism[edit]

Whether for religious purpose or war, it is apparent from the 2009 study that the humans at the site of Herxheim were butchered and eaten.[1] Not only were cut marks found on locations of the skeleton that are made during the dismemberment and filleting process, bones were also crushed for the purposes of marrow extraction, and chewed. Besides the fresh-bone fractures present on many bones, "[processing] for marrow is also documented by the presence of scrape marks in the marrow cavity on two fragments."[1]

Skeletal representation analysis revealed that many of the "spongy bone" elements - such as the spinal column, patella, ilium, and sternum - were underrepresented compared to what would be expected in a mass grave. "All these observations are similar to those observed in animal butchery."[1] Additionally, preferential chewing of the metapodials and hand phalanges "speak strongly in favour of human choice rather than more or less random action by carnivores".[1]

The number of people concerned at Herxheim obviously suggests that cannibalism for the simple purpose of survival is highly improbable, all the more so as the characteristics of the deposits show a standard, repetitive, and strongly ritualised practice.[1]

A detailed study published by the excavators in 2015 estimates that the site contains the scattered remains of more than 1000 individuals, all of whom were butchered and eaten.[6] More than a third of the dead were juveniles, ranging from newborns to teenagers. Both men and women were among the victims, but in most cases sex determination was not possible.[7] The age distribution of the corpses is typical of communities living in preindustrial times, but deviates from the typical age-of-death distribution in such societies; therefore the excavators consider it likely that the victims were deliberately killed rather than dying a natural death.[8]

The evidence indicates that the bodies were cooked, probably by spit-roasting them whole (including the heads) over open fires. Both flesh and bone marrow were eaten, and the skulls were processed into cups.[9] An analysis of the bones shows that the victims had lived in a variety of geographical regions – some might have lived near Herxheim, others in other regions populated by the Linear Pottery culture, and a third group had lived in mountainous areas not inhabited by members of that culture.[10] The treatment of the skull cups (which were used as drinking vessels while feasting on their former owners and then discarded) suggests that the dead were regarded as enemies or outsiders rather than estimated relatives or community members (in the latter case, skull cups were sometimes made as well, but kept as honoured relics).[11]

Two alternative explanations have been suggested for how people from quite different regions ended up in Herxheim, where their lives were violently ended and their bodies consumed. One is that warriors from the region around Herxheim raided other territories and brought captives back for consumption, which would mean that the site was an important centre of a successful warrior culture. The other explanation is that the site was a major religious centre where human sacrifices (followed by cannibalism) took place and which was visited by people coming from various, sometimes faraway areas, some of whom were killed there. In this case, too, the excavators suspect that the sacrificed were brought as captives or slaves to the site, considering it unlikely (though not completely impossible) that people would have voluntarily travelled towards a faraway region to be sacrificed and eaten there.[12]

Earlier alternative hypotheses: secondary burial and necropolis[edit]

The original conclusion from the earlier 2006 study was that the site of Herxheim was a ritual mortuary center – a necropolis – for the LBK people of the area, where the remains of the dead were not just buried, but for reasons unknown, destroyed. They considered the large number of corpses as well as the transportation of pottery and flint from distant areas to the site further arguments for this conjecture.[3]

The projection of the number of individuals present ... to a probable total of 1,300 to 1,500 rules out the possibility of a local graveyard — and points a regional centre at Herxheim to which human remains were transported for the purpose of reburial.... To organise the transport not only of stone tools and pottery but also of human bones and partial or maybe even complete corpses implies an efficient organisational and communication system.[3]

The authors of this study suggested that Herxheim was a site for a type of burial known as secondary burial, which consists of the removal of the corpse or partial corpse and subsequent placement elsewhere. They concluded this from the lack of complete, articulated skeletons in the majority of the burials. Another discussed possibility was that of sky burial, in which the corpse is exposed to the elements and many bones are carried off by scavengers.[1][3]

The later 2009 study rejected these possibilities in favour of the cannibalism hypothesis. This resulted in a controversy about which explanation was more plausible, with other archaeologists maintaining that the evidence better fits a scenario in which the dead were reburied following dismemberment and removal of flesh from bones. "Evidence of ceremonial reburial practices has been reported for many ancient societies."[13]

However, in their later more detailed study the excavators point out that that the human remains were put into the ditches quite shortly after their death (probably no more than a few days), when various body parts were still kept together by soft tissue. This rules out secondary burials and sky burials, since in either case more time would have passed before the deceased would have found their final resting place at Herxheim. It also indicates that the buried died (likely by being killed) at or near Herxheim rather than in the regions where they had lived (which were in some cases far away).[14] Moreover, the specific treatment of the bodies, such as the splitting of bones to extract the marrow, is typical for cannibalism and does not fit the observed patterns of secondary burials, and various other traces show that the corpses were processed in the same way as animals that are butchered, roasted and eaten. Therefore they consider cannibalism the only plausible explanation.[15]

See also[edit]

- Fontbrégoua Cave, another noted Neolithic site with evidence of potential cannibalism

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Boulestin, B.; et al. (2009). "Mass cannibalism in the Linear Pottery Culture at Herxheim (Palatinate, Germany)". Antiquity. 83 (322): 968–982.

- ^ Boulestin & Coupey 2015, pp. 101, 115, 123, 126.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Orschiedt, J.; Haidle, M. N. (2006). "The LBK Enclosure at Herxheim: Theatre of War or Ritual Centre? References from Osteoarchaeological Investigations" (PDF). Journal of Conflict Archaeology. 2 (1): 153–167. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-09-27.

- ^ a b Projekt Herxheim (German language).

- ^ Johnson, E. (1985). "Current developments in bone technology". Advances in Archaeological Method and Theory. 8: 157–235. JSTOR 20170189.

- ^ Boulestin & Coupey 2015, pp. 101, 115.

- ^ Boulestin & Coupey 2015, pp. 102–106.

- ^ Boulestin & Coupey 2015, pp. 109–114.

- ^ Boulestin & Coupey 2015, p. 115.

- ^ Boulestin & Coupey 2015, p. 123.

- ^ Boulestin & Coupey 2015, pp. 123–124.

- ^ Boulestin & Coupey 2015, p. 126.

- ^ Bower, Bruce (4 December 2009). "Controversial Signs of Mass Cannibalism". Wired. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- ^ Boulestin & Coupey 2015, p. 26.

- ^ Boulestin & Coupey 2015, pp. 40–46, 63, 69–70.

Further reading[edit]

- Boulestin, Bruno; Coupey, Anne-Sophie (2015). Cannibalism in the Linear Pottery Culture: The Human Remains from Herxheim. Oxford: Archaeopress.

- Projekt Herxheim: Ongoing list of related publications in German, English, and French.

- Settlement Site Hints at Mass Cannibalism: Discovery News