It's no secret that scientists can be corrupted - in the past, researchers have purposefully hidden data on climate change, and the dangers of sugar, just to name a few.

But while people can be bought, the scientific method itself - the idea that a hypothesis must be observed, tested, replicated, and the results then published in a peer-reviewed journal - has always remained a beacon of objectivity, assumedly free of bias by its very nature.

Unfortunately, in recent years scientific publishing has been running into serious trouble.

Through predatory journals, publication bias, and a publish-or-perish mentality, the way we practice the scientific method has been corrupted right under our noses - we're at a point now where some studies can't even be reproduced.

More recently, it's become clear that the system for publishing results on evidence-based medicine is broken, too.

On paper, evidence-based medicine is a good thing. It's how we get life-saving treatments and medication, and it's the requirement for any new drugs to be based on solid, peer-reviewed research.

But this assumes that peer-reviewed research will be unbiased, and that's not always the case.

Just last week, a report concluded that many clinical trials are greenlit based on a shockingly poor evidence base, sometimes without any published data.

Now nephrologist Jason Fung has taken to Medium to highlight even more damning evidence against the journals we rely on to print the best academic research.

His article is a summary of information that's already out there, published in the lead up to a presentation to the European Parliament this week. But seeing it all in one place is confronting.

Most shocking: medical journal editors are paid huge sums by pharmaceutical companies each year.

This is something most of us already know - we see the sponsored pens and all the fancy conferences doctors go on thanks to 'big pharma'.

But that's only a small part of it. The industry also just hands them money directly.

A paper published last year in the British Medical Journal examined how much money editors of the world's most influential medical journals were taking from industry sources.

Of the journals that could be assessed, 50.6 percent of editors were receiving money from the pharmaceutical industry - in some cases, hundreds of thousands of dollars.

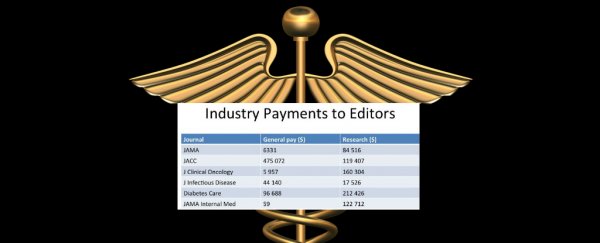

Here's just a small highlight showing editor payments received in 2014 - the amount on the left is direct payments, and the 'research' payments on the right are less regulated, usually made in the form of expensive research trips.

(Liu et al., BMJ, 2018)

(Liu et al., BMJ, 2018)

The average 'in hand' payment in 2014 alone was US$27,564, plus research funds.

Worst on that list is the Journal of the American College of Cardiology (JACC), where 19 of its editors received, on average, US$475,072 personally and another US$119,407 for 'research'.

And that's not even mentioning the amount of reprint money journals get whenever they publish a study that supports a pharmaceutical company, and the company pays for hundreds of copies to send out to doctors.

The Lancet earns 41 percent of its income from reprints, and the American Medical Association gets 53 percent.

"The medical profession is being bought by the pharmaceutical industry, not only in terms of the practice of medicine, but also in terms of teaching and research," said the late Arnold Relman, a former editor-in-chief of the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) in 2002. He passed away in 2014.

"The academic institutions of this country are allowing themselves to be the paid agents of the pharmaceutical industry. I think it's disgraceful."

Why does all this matter? In the face of these kind of numbers it's easy to see why journal editors would choose to print research that supports products of these companies, and ignore the evidence that goes against them.

And that's exactly what's happening.

Research backed by the pharmaceutical industry is far more likely to have positive results published than government-funded science.

Not only that, but negative results are often ignored. In a 2008 study that Fung cites, 36 out of 37 studies that were favourable to antidepressants were published.

In comparison, only 3 out of 36 studies that were not favourable to the drugs made it to print.

That means if you were to solely look at the published literature, you would think an overwhelming 94 percent of studies show these antidepressants work, when, in reality, only 51 percent of the studies conducted were actually positive.

Seeing these numbers in black and white is sobering.

Despite grumbles of 'big pharma', most of us still put our faith in the peer-review process, confident that the scientific method will guide us in the right direction regardless of people's own bias.

Unfortunately, the results provided to us by the scientific method are only as good as the editors that gatekeep them.

This is why more and more researchers are publishing their work in pre-print and open-access journals, where the world can see their research for free.

There's also a push to get organisations to publish all valid results, even if they're negative.

We have a long way to go, but it's only by acknowledging a system is broken that we can begin to fix it.